Owning that first rental property is a huge milestone for investors. It lets you dip your toe into the market, gain experience in property management, and build confidence in your judgement. But for ambitious landlords, the first property marks just one step on a larger journey toward passive income and financial independence.

But it’s not always easy to expand your portfolio. Most investors face two main obstacles: capital and capital gains. The former is simply a question of where you are going to get the money for your second (and third, and fourth) properties? The latter is a question of, how much of your wealth will you be able to hold onto in the face of capital gains taxes that can run as high as 23.8%?

Happily, there’s a solution that addresses both those concerns at the same time. A semi-obscure tax provision called the 1031 exchange allows investors to defer that punishing capital gains tax liability, and reinvest every penny of their hard-earned profit in their next investment. But like a lot of the tax code, it comes with a list of potentially confusing rules attached. Let’s go over some of the details of the 1031 exchange, and figure out if and when it’s right for you.

What Is a 1031 Exchange?

A 1031 exchange, inventively named after the section of internal revenue code that describes it, allows you to essentially trade or “exchange” one investment property for another, without paying capital gains taxes on the profits from the sold property.

The strategy is simple: you repeatedly swap out your income properties to upgrade your cash flow. When you first start investing in real estate, you might buy a small single-family rental that yields $150/month. After a couple years, you sell it and put the proceeds toward a three-unit rental that yields $400/month. A few years after that, you sell the triplex and roll the profits into a six-unit apartment building. Then a ten-unit, then a 15-unit, and so forth, each of which generates far more cash flow than the prior property.

All the while, you don’t pay a cent in capital gains taxes. Which helps you build momentum in your investments.

Say you bought a property at $100,000, and it’s now worth $300,000. If you sold that property without using a 1031 exchange, you could lose 23.8% of that $200,000 profit, or $47,600, to Uncle Sam. That could seriously hamper your efforts to use that money to upgrade your portfolio: a 20% down payment of $120,000 gets you a much less valuable property than a 20% down payment of $200,000.

And yes, you can still take rental property tax deductions before, during, or after doing a 1031 exchange.

Who Qualifies for 1031 Exchanges?

By using a 1031 exchange means you can defer your capital gains taxes, and invest that entire $200,000 of profit. But as with every legal loophole, some restrictions apply. If you can’t comply with at least three out of the next four criteria, you probably aren’t eligible for a 1031 exchange.

1031 Exchanges: For Real Estate Investors, Not Homeowners

A 1031 exchange is a tool that’s meant for investors. The bad news: in most cases, you can’t do a 1031 exchange on your primary residence.

The good news? You don’t need to, as the IRS already offers a generous capital gains exemption for your primary residence! The first $250,000 of profits are tax-free ($500,000 for married couples), if you’ve lived in a property for at least two of the last five years.

Property of Equal or Greater Value

You can’t use a 1031 exchange to defer your capital gains tax liability if you’re planning to simply sell off your investment property and pocket the profits. Like-kind exchanges are a tool for investors who are trying to level up their portfolio. Most commonly, investors who use a 1031 exchange take the entire proceeds from their initial sale, and put it down as a 20% down payment on a larger investment property.

If the purchase price of the new property is lower than the sales price of your old property, expect to pay capital gains taxes on the difference (more on boot shortly).

1031 Exchange Must Be “Like-Kind”

The 1031 exchange has a “like kind” rule, which means the property being relinquished has to be similar to the property being purchased. But this rule is very forgiving; as long as you’re buying and selling investment property, you’re very likely to meet the “like kind” requirements.

The only circumstances where you might run into trouble is if you were trying to use a 1031 exchange to sell investment property and reinvest the money in, say, stocks.

1031 Exchange Time Limits

Since this is supposed to be a trade of properties, there are strict time frame limits on how long you have to execute your 1031 exchange.

You’ll have a 45 day “identification period” after you sell your initial property to identify subsequent investment properties. That means you’ll likely want to start looking at potential properties well before you close on that initial sale.

If that sounds daunting, there’s also some good news here. Since finding the perfect exchange candidate while you’re on the clock can be a challenge, the rules of the 1031 exchange allow you to identify up to three replacement properties, to give yourself a little wiggle room. You don’t have to buy all three of the properties, but you do have to buy at least one. And if you buy multiple replacement properties, the total value of them must be equal or greater than the sale price of the initial property.

One last time-related rule: you must complete the purchase of your replacement property within 180 days of selling the initial property. Even one day longer and you risk losing all the tax benefits of the 1031. Fortunately, the IRS allows you to identify up to three potential replacement properties, as we all know real estate deals fall through all the time.

How Do 1031 Exchanges Work?

You decide you want to move forward with a like-kind exchange. How do you go about it logistically?

The law states that you can’t actually oversee the exchange yourself. You can’t hold the proceeds after selling one property but before buying the new one, in a delayed exchange. Neither can your parents, siblings, children, or spouse, or even your existing “agent” such as your attorney, real estate agent, or property manager.

The actual 1031 exchange will actually be carried out by a qualified intermediary (QI), a company set up for the specific purpose of carrying out 1031s. You, the seller, don’t ever come into possession of the proceeds of the initial sale; that property is sold by the qualified intermediary, who uses the money to buy the replacement property on your behalf, and then transfer the deed to you. From the investor’s perspective, it really is a trade; they relinquish the initial property to the QI, who then gives them the deed to the replacement property.

The qualified intermediary also handles all the tax forms, makes sure the exchange meets IRS guidelines, and can advise you on meeting the many affiliated deadlines so you can definitely secure the tax benefits. You’ll have to pay for these services, but the fees are pretty reasonable; nationally, QI services cost, on average, between $600 and $1,200. That can go up if you’re doing a more complicated reverse exchange, or an exchange involving multiple properties.

Boot, Cash and Debt

If you have cash left over after doing a deferred exchange, the IRS taxes it as capital gains. This leftover is known as “boot,” a ye-olde-English word meaning “something in addition to” — you know this word from the expression “to boot.”

But where boot gets more complicated is the change in debt, not cash. If you take out less debt on the replacement property than you had on the relinquished property, that difference in debt also gets taxed as gains.

For example, say you sell your old property for $150,000, of which $100,000 went to pay off your mortgage, and the other $50,000 went to the qualified intermediary to hold in escrow. (We’re ignoring closing costs for the sake of simplicity, so stop nitpicking.) You don’t just need to spend the $50,000 in cash when you buy the new property; you also need to meet the same debt level.

Sound complicated? It’s not: all you have to remember is that the new property must cost at least much as the original property. You can’t replace a $150,000 property with a $50,000 property, just because your cash profits were $50,000.

1031 Exchanging Multiple Properties

Ready to get more advanced?

First, there’s no limit to the number of 1031 exchanges you can do in a given year. Swap as many properties as you want!

Second, you can 1031 exchange several lower-cost properties into one expensive property. For example, you could sell two $200,000 properties and 1031 exchange them into one $400,000 property.

Third, you can do the reverse as well. You can 1031 exchange one property into multiple cheaper properties. Reversing the example above, you could sell a $400,000 property and 1031 exchange it into two $200,000 properties.

Pretty awesome, right?

Depreciation & 1031 Exchanges

The IRS allows landlords to depreciate their rental properties, or spread certain tax deductions over multiple years. Investors can depreciate the cost of the building itself (not the land), and some closing costs, over the first 27.5 years of ownership. Landlords can also depreciate capital improvements over time as well (use our free rental property depreciation calculator to run the numbers on your own property).

When landlords sell a rental property that they’ve depreciated, that tax break gets reversed. The investor owes depreciation recapture, taxed at regular income tax rates, although capped at 25%.

Taxpayers can, however, defer paying depreciation recapture taxes alongside capital gains taxes using a 1031 exchange. At least when they buy a like-kind property, with a building on it — if the do a 1031 exchange to swap a rental property for vacant land with no building, they still have to pay depreciation recapture, because there’s no building to depreciate on the new property.

Can You Use a 1031 Exchange on Vacation Homes?

While not designed for second homes, 1031 exchange rules do allow you to convert them into vacation rentals and defer capital gains taxes when you sell them.

For each of the two years (12-month periods, not calendar years) before you sell the property, you must meet two requirements:

1. The property must be rented for at least 14 days at fair market rents, and

2. You can’t use the property personally for more than 14 days or 10% of the time it was rented (whichever is greater).

In other words, you must legitimately become a Airbnb landlord — it must truly be a vacation rental, not a second home.

Do that for two years, and you can defer taxes on the property and put the proceeds toward another investment property.

Can You Move Into a Property After Doing a 1031 Exchange?

When you exchange properties, the IRS expects you to buy a new income property for investment purposes. Still, life happens, and the IRS does allow you to convert a rental home to your primary residence.

Which, in turn, would qualify the property for the $250,000 home exclusion for capital gains taxes ($500,000 for married couples).

The same rules apply to converting an investment property to personal use, just in reverse. After going through the 1031 exchange process, you must use the property for real estate investment purposes for at least two years. That means at least 14 days of it being rented at fair market value in each of those two years, and you can’t use the property personally for more than 14 days or 10% of the time it was rented, whichever is greater.

After those two years, you can move in. But remember, you must live in the property yourself for at least two years before it qualifies for the primary residence exemption from capital gains taxes. That means a minimum period of four years of ownership, between buying a property through a 1031 exchange and when you could first sell it as a residence and get the exemption.

You’re Eligible — Does It Make Sense for You?

Just because you meet all the requirements for a 1031 exchange doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s in your best interests. Here are some important factors to consider.

What Is Your Tax Burden?

Some investors are so focused on using a 1031 exchange to upgrade their holdings that they haven’t even bothered to calculate their tax liability.

Let’s say you’re selling a plot of land. Since you can’t claim depreciation on land — only on structures that actually wear out, decay, or fall apart — you won’t have to worry about depreciation recapture at the time of sale, which is one of the biggest factors that can inflate an investor’s tax bill. In this case, it may not even make sense for you to pursue a 1031 exchange over a straightforward sale.

Similarly, let’s say you’re selling your rental property in a state like New Hampshire, Florida, Alaska, or Tennessee. Those states, among others, don’t collect capital gains taxes, so you wouldn’t be deferring anything.

Make sure you figure out your exact tax liability before you consider strategies to defer it. It might not be that bad!

Do You Need Cash?

To defer all your capital gains taxes, you’ll have to invest the entire proceeds from your property sale. While a partial exchange is an option, you’ll have to pay taxes on however much you cash out, which can radically skew the cost/benefit equation. If you might need liquidity in the near future, a 1031 might be a great option, since you would never actually hold any cash from the sale.

Do You Have Actual Gains to Defer?

This may sound obvious, but if the property you’re selling hasn’t appreciated since you purchased it, a 1031 exchange is going to have very limited advantages over a straightforward sale. In the same vein, small gains are going to offer small deferral benefits.

Are You a House Flipper?

House flippers are usually ineligible for a 1031, even though they seem to fit all the requirements. After all, a house purchased to be flipped is clearly an investment property.

But a closer reading of the 1031 exchange regulations reveals an inconvenient exception for house flippers; property “held primarily for resale” does not qualify for a 1031 exchange. The regulations also specify that the sold property must have been “used in a trade or business,” i.e. produced income while you owned it.

The 1031 exchange is designed to defer long-term capital gains taxes, not regular income taxes. So the only way that house flippers can use a 1031 is to hold the property for a year, rent it out, and then trade it up.

Final Thoughts

Like-kind exchanges offer a great way to upgrade your real estate portfolio tax-free. But they’re not without their wrinkles, and they do require that you bring in a facilitator to hold funds in escrow and oversee both transactions.

Consider 1031 exchanges a more advanced real estate tax strategy, to try only after you’ve mastered the fundamentals of real estate investing.♦

Have you ever tried a 1031 exchange? If so, what were your experiences? If not, how do you intend to work them into your real estate investing strategy?

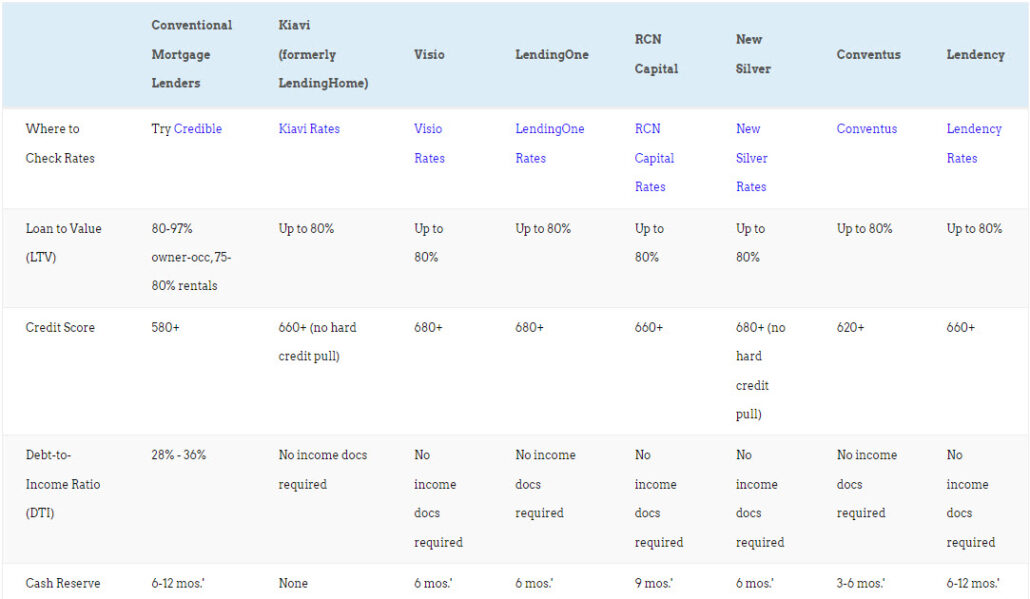

Read llc mortgage loan requirements.

Read does california have rent control?

Great overview of 1031 exchanges. I’m hoping to do this with a property I don’t love, and parlay it into a property with better cash flow.

I’ll keep you posted!

Thanks Sally, let us know how it goes!

Whether the 1031 exchange is profitable or not depends on the situation, in my case I couldn’t exchange cause I got no secondary residence now.

It does depend on the situation. But you don’t need a second residence to do a like-kind exchange – you swap an existing rental property for a new one. In fact, 1031 exchanges aren’t designed for second homes at all.

Hope that clarification helps Bill!

Really good article. Unfortunately, I’m flipping a residence and can’t get access to 1031, just like you described.

Would a 1031 exchange work for selling a multi family investment property and using the profits for purchasing a plot of land and building an investment property?

This is great! Thank you for sharing this information.

Glad you found it useful Miss MJ!

I haven’t tried a 1031 exchange yet. But I’m thinking about it for my next deal. Hoping to upgrade my duplex to a fourplex.

Keep us posted on how it goes Joanna!

Excellent content as always.